The digital world has made it much easier to buy and consume entertainment.

Whether it’s a movie, music track, or book, a shiny “buy now” button is usually just a few keystrokes away.

Millions of people have now replaced their physical media collections for digital ones, often stored in the cloud. While that can be rather convenient, it comes with restrictions that are unheard of offline.

This is best illustrated by an analogy I read a few years ago in a research paper by Aaron Perzanowski and Chris Jay Hoofnagle, titled: “What We Buy When We Buy Now.”

It goes something like this:

Imagine purchasing a book on Amazon, which is promptly delivered to your home. You put it on the bookshelf so you can crack it open on a rainy day. However, when you wake up the next morning there’s an empty spot on the shelf. The book disappeared.

In an email, Amazon customer service explains that it was recalled at the behest of a copyright holder. They quietly dispatched a drone, which entered your home at night to take the book away, and issued a refund.

This may sound utterly crazy, but in the digital world, it’s a reality. A few years ago, Amazon remotely wiped several books from customers’ Kindle e-readers because of a copyright complaint.

When these Amazon customers woke up the following day they found that the books they thought they owned, which ironically included George Orwell’s “1984,” were no longer theirs. Just like that.

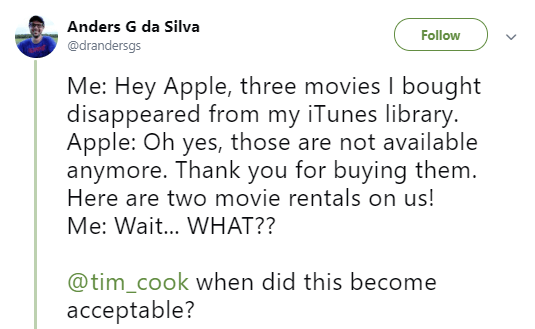

This issue is much broader than just Amazon of course, there are restrictions on most of the online media you can “Buy Now.” This was brought to the forefront again this week when Anders G da Silva noticed that Apple had removed three movies from his iTunes library. Movies he bought.

Apple informed him that the movies were not accessible to “redownload” because they were no longer offered by the Canadian iTunes Store. Apparently, Apple’s license to distribute the titles has expired.

In this case, it only applies to the copies that were stored in the cloud. Any movies already downloaded on a device should work fine. While not widely known, this is covered by Apple’s terms of service.

“Content may not be available for Redownload if that Content is no longer offered on our Services,” iTunes’ terms read.

Technically it makes sense. If Apple no longer has a license, they can’t distribute the files. But wouldn’t it make more sense to adapt these licensing agreements to the modern time? Why not allow indefinite redistribution to people who previously bought something legally?

Today’s reality is that ‘owning’ something in the digital world is something entirely different than owning something offline. A movie studio or book publisher can’t barge into your house and take a Blu-ray or book, but online it’s an option.

It is rare that downloaded media actually disappears from people’s devices, as happened in the aforementioned Amazon case, but there are other ‘digital’ restrictions too.

If you buy a Blu-ray disc of the latest “Pirates of the Caribbean” movie you are free to lend it to a friend, or even sell it on eBay after you’ve watched it. In the digital world that’s often not an option. You don’t really own what you buy.

This brings us back to the research paper I mentioned earlier, which was previously featured by the LA Times.

The researchers examined how the absence of the right to resell and lend affects people’s choice to buy. They found that, among those who are familiar with BitTorrent, roughly a third would prefer The Pirate Bay over Apple or Amazon if they are faced with these limitations.

These rights restrictions apparently breed pirates.

“Based on our survey data, consumers are more likely to opt out of lawful markets for copyrighted works and download illegally if there is no lawful way to obtain the rights to lend, resell, and use those copies on their device of choice,” the researchers concluded.

The paper in question is two years old by now, but still very relevant today. While we don’t expect that anything will change soon, people should at least be aware that you don’t always own what you buy.

It’s an illusion.

The digital world has made it much easier to buy and consume entertainment.

The digital world has made it much easier to buy and consume entertainment.