With more ways to consume multimedia content than ever before, locking down music, movies and TV shows continues to be big business online.

The key way this is achieved is via Digital Rights Management, which is often referred to by the initials DRM. In a nutshell, DRM is achieved via various technologies which dictate where and when digital content can be accessed.

While DRM is popular with providers seeking to exercise control over their content while preventing piracy, DRM is viewed by some consumers as a restrictive practice that only inconveniences genuine customers.

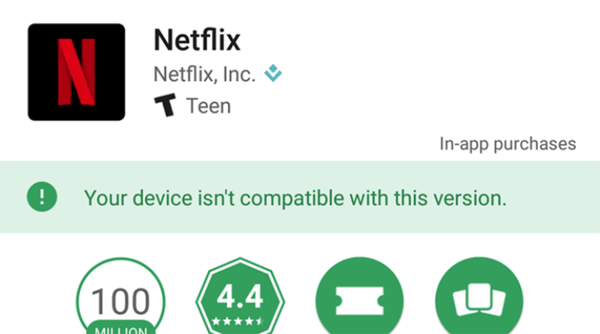

This weekend, further fuel was poured on that fire when Android Police reported that subscribers to Netflix who access the service via ‘rooted’ Android devices can no longer download the official Android app from Google Play.

“With our latest 5.0 release, we now fully rely on the Widevine DRM provided by Google; therefore, many devices that are not Google-certified or have been altered will no longer work with our latest app and those users will no longer see the Netflix app in the Play Store,” Netflix confirmed.

Widevine is a company owned by Google and its DRM platform claims to be able to “license, securely distribute and protect playback of content on any consumer device.”

To meet those claims, Google requires that its partners running Widevine-protected systems live up to its standards by becoming a Certified Widevine Implementation Partner (CWIP). A part of that requires that software platforms are only allowed to run on approved hardware/software combinations.

It is no surprise that ‘rooted’ Android devices fail to meet those requirements. When a user ‘roots’ their device they effectively gain administrator rights, which allows them to get into the nuts and bolts of the machine and carry out modifications.

Many users do this to innocently customize how legally purchased hardware performs, including making the Netflix experience better, as illustrated by the Google Play review on the right.

However, it’s clear that this kind of low-level access also has the potential to make piracy easier, whether that’s through the defeating of licensing checks or indeed the wholesale extraction of video content.

For this reason, ‘rooted’ devices raise red flags, not only for content delivery companies like Netflix and partners Google, but also for certain banking companies whose apps won’t run on devices with extended administrator capabilities. These companies want a predictable and secure environment in which to offer their services and ‘rooted’ platforms do not offer that.

The problem, however, is that for every potentially malicious user, there are many thousands of others who want to have the freedom to run a ‘rooted’ device while also being a legal consumer of Netflix. For them, the frustration could even boil over into what DRM was designed to prevent in the first place.