Every year, dozens of piracy studies and surveys appear online. These can help to signal new trends and changes in user behavior.

When done right, research can be a valuable tool to shape future law or to direct enforcement efforts and priorities.

This also appears to be the goal of a recent report published by PRS for Music, which was put together by Incopro. The report looks at the current state of the online piracy landscape and how it has developed over time. The conclusions from this endeavor are somewhat surprising.

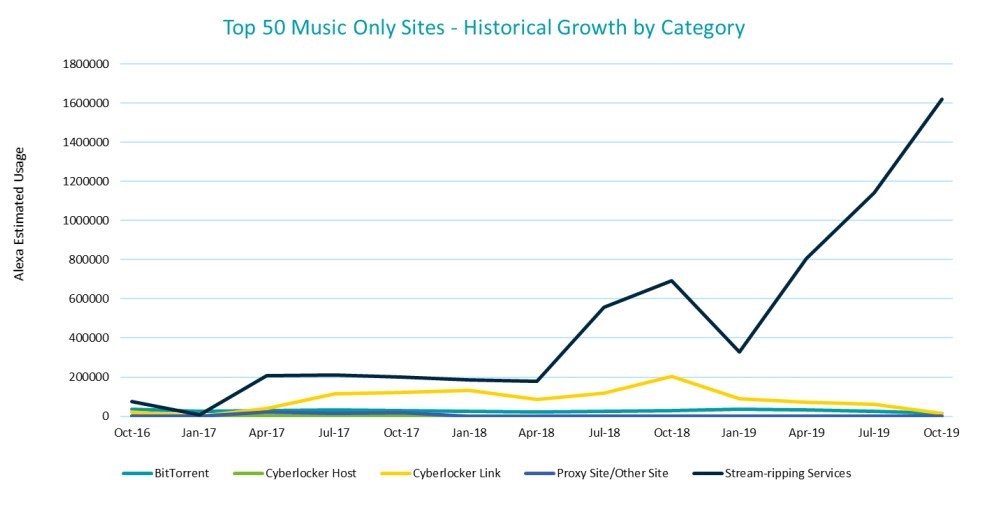

1390% Increase in Stream-Ripper Traffic

The headline figure, which was taken over by dozens of mainstream news outlets, is that stream-ripping piracy has grown explosively. Between 2016 and 2019 the use of stream-ripping services in the UK increased by no less than 1390%.

This unprecedented boom is unexpected. At TorrentFreak, we keep a close eye on piracy statistics, but we never saw this coming. Intrigued by this mysterious traffic boom, we decided to take a closer look, starting with the data sample.

The PRS report is based on traffic estimates to a few dozen of the most popular sites. The appendix provides an overview of the sites that were considered for the study. This includes many of the expected names, including The Pirate Bay, Openload, and Flvto.biz. However, there are also a few unusual suspects.

French ISP and Huawei Listed as Top Pirate Sites

For example, the website of the French Internet provider Free.fr is seen as one of the top pirate sites in the UK. This is strange, as the site is in French and not at all dedicated to sharing pirated music. Instead, it’s used to sell Internet subscriptions.

The official website of the Chinese technology company Huawei is also listed among the top 50 pirate sites. Why remains a mystery, but it’s hard to see what the appeal of club.huawei.com is to UK visitors, especially since the site is in Chinese.

These two are not the only odd entries. The list also includes the website of the popular torrent client uTorrent, which doesn’t link to or host any infringing content. The same is true for the link shortener sh.st, which simply forwards people to URLs.

At the same time, the top 50 also features a lot of dead pirate sites, which haven’t been online for years. This includes some we have never heard of, such as usd.bravo-dog.com, which appeared to be associated with malicious popups in the past.

While it’s possible that some of these sites have links to pirated content somewhere, they shouldn’t be listed among the top pirate sites. Especially not when considering, for the purpose of the report, all traffic to the sites is said to be copyright-infringing.

Flaws Aside, What’s Driving the Reported Traffic Boost?

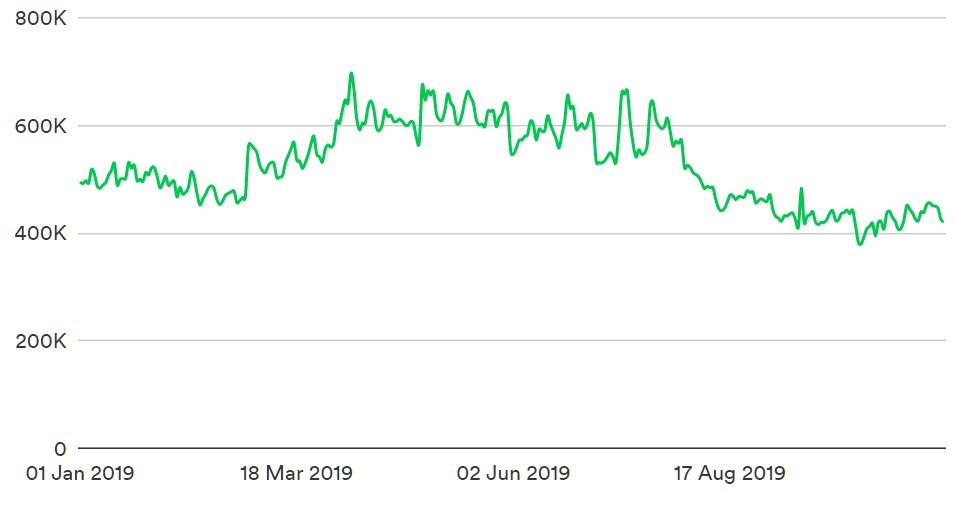

We could stop here, as the above suggests that there are critical flaws in the dataset. However, we remain intrigued by the reported 1390% boost in the usage of stream-ripping sites in just three years. According to the research, stream-ripping now dwarfs any other form of music piracy, as illustrated below.

This boom started somewhere in 2017 but it really took off between January and October 2019. In just nine months, the usage of stream-ripping services in the UK grew by more than 500%.

It’s not entirely clear why this happened and the PRS report provides no answers either. Instead, the report simply attributes this effect to one site, y2mate.com, which suddenly became very popular.

“Later in 2019 we can see another surge, this is likely due to the emergence and popularity of the site y2mate.com, which has the highest usage of all sites. All other services remained fairly steady,” it reads.

Google Trends and Other Stream Ripper Data

This is an odd conclusion. Stream ripping sites don’t just become very popular. It all starts with an increase in demand that drives more people to visit these sites. This report suggests that in 2019, a lot of UK visitors suddenly became interested in stream-ripping, and they all went to the same site.

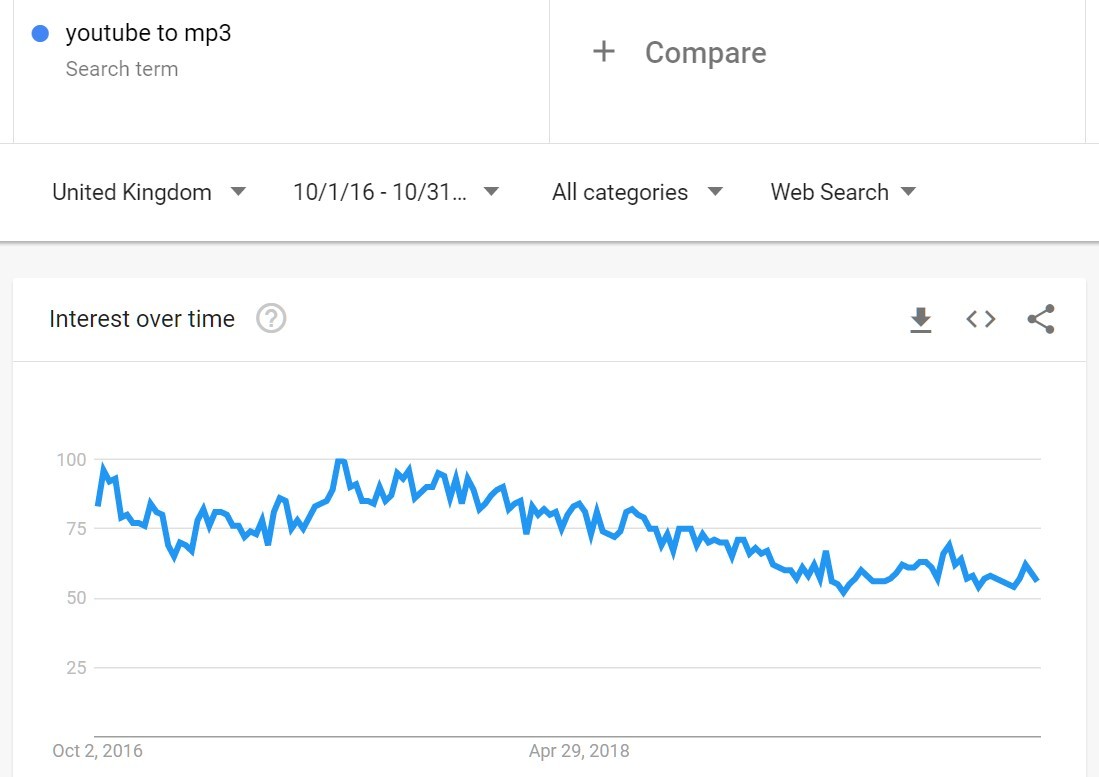

We tried to find evidence for this “boom” through Google trends. According to the PRS report, roughly 50% of all traffic to these sites comes from search engines. So, one would expect the search volume for ‘YouTube to MP3,’ a popular term for these sites, to increase as well.

This is not what we see in Google trends. UK searches for ‘YouTube to MP3,’ which is good for 10% of all traffic to y2mate.com, according to PRS, remained stable in 2019. In fact, the trend since 2016 goes down instead of up.

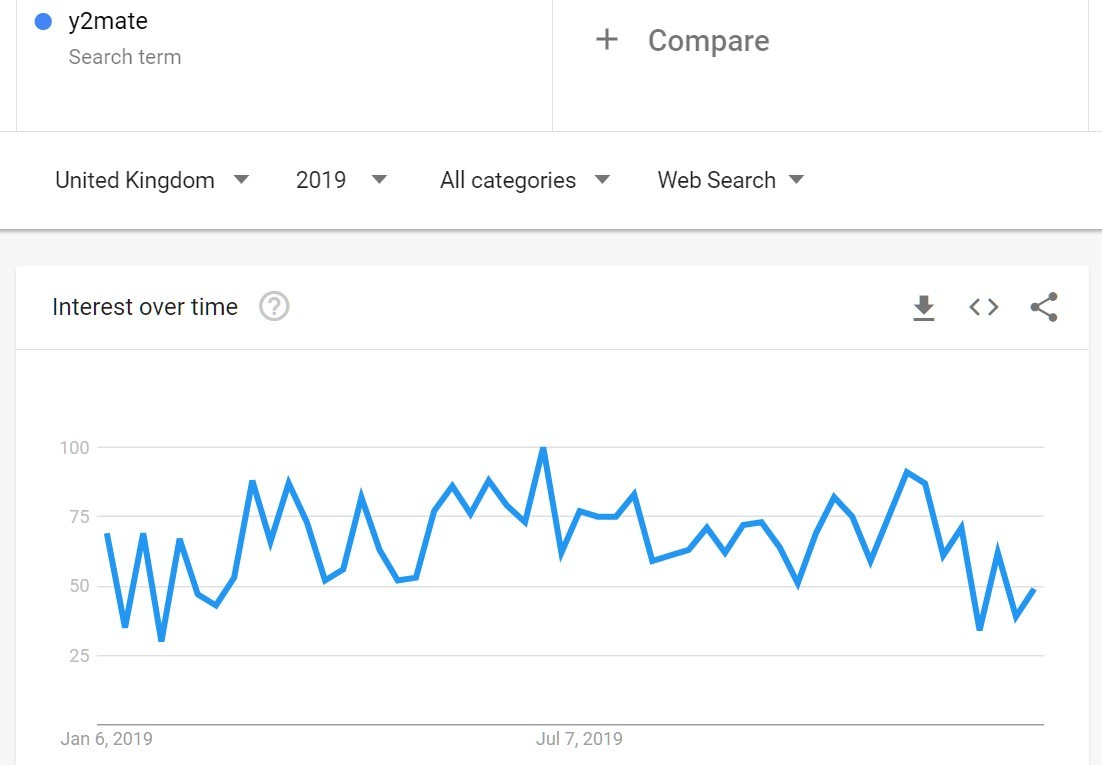

Perhaps people might search for the site’s name instead? We considered this as well, but despite the reported explosive growth of y2mate.com traffic in 2019, the search volume for the keyword “y2mate” didn’t change.

Could it be that we’re missing something here? In search for a replication of the reported increase, we looked at the traffic numbers piracy tracking firm MUSO.com reports for stream-ripper sites in the UK.

We specifically zoomed-in from January to October of 2019, where PRS reports a ~500% increase in stream-ripper traffic. However, there is no such increase in MUSO’s data*. If anything, the trend is going down.

TorrentFreak spoke to MUSO’s CTO James Mason who explained to us that their dataset is different from that of Incopro. The latter, which is used for the PRS report, uses a limited number of sites, which can more easily result in biased results.

Biased Data?

“We can see that in January 2018, just 25% of our music stream ripper traffic is on domains included in the Incopro domain list. This rises to 68% by October 2019, indicating that the Incopro stream ripping domain list is biased towards more recently active sites.

“This bias is likely the main reason why their data shows a dramatic increase, whereas our data includes a fuller coverage of stream ripper sites within the earlier reporting period and so we have measured the more complete (higher) traffic in earlier years,” Mason adds.

There are other differences in methodologies as well. For example, MUSO only looks at music-related traffic to the domains, while the PRS report doesn’t make that distinction.

Based on all data that are reviewed by us, we find it hard to believe that the dramatic increase in stream-ripping usage actually exists.

We have shared our findings with PRS for Music and asked for a comment on our findings. PRS, with relayed several questions to Incopro, did not specifically respond to our question about the legal sites that were flagged as piracy portals. Not did they respond to our question about the spectacular boost in Y2mate traffic.

Like MUSO, PRS and Incopro did point out that there are differences between research methodologies. The PRS report only looks at a relatively small number of pirate sites.

“The key analysis [of this study] is of the Top 50 Music-Only piracy sites and is based on cumulative data collected between October 2016 and October 2019. As such, sites which are active for only a small portion of this time period may not feature in the analysis of high-usage sites. We acknowledge in the report that many sites from the original 2016 landscape are now offline – demonstrating the effectiveness of enforcement approaches over this period, and showing how the landscape from 2016 has evolved,” the companies inform us.

“Whilst different analyses may give differing results, it is clear that stream-ripping remains a serious and growing problem for music and we hope that this report can contribute to the debate on how to address it,” they add.

Limited Research Shouldn’t Used to Create Policy

The problem, however, is that the report is out in public now. This means that it will likely be used as input for future policy decisions. In fact, the report’s figures we already cited in a recent publication from the UK Intellectual Property Office, without a mention of any possible caveats.

That said, the goal is not to show that one tracking company or methodology is superior to another. All research comes with flaws, including MUSO’s findings. However, it’s obvious that these reports should be properly scrutinized, especially when legal sites are flagged as piracy portals, and when there are massive shifts in piracy habits.

—

* Note: MUSO data includes an algorithm change on August 1, 2019, but that appears to have had a minimal impact on the reported stream-ripping traffic.

Every year,

Every year,